Her first plough-furrow opened the earth (Tellus' realm) to the world of men and created the first field and its boundary; she thus determined the course of settled, lawful, civilised life. She mediated between plebeian and patrician factions. She oversaw the transition of women from girlhood to womanhood, from unmarried to married life and motherhood and the growth of children from infancy. Despite her "chthonic" connections to Tellus, she was not, according to "Spaeth", an underworld deity. Rather, she maintained the boundaries between the realms of the living and the dead.

Given the appropriate rites, she would help the deceased into afterlife as an underworld shade ("Di Manes"): otherwise, the spirit of the deceased might remain among the living as a wandering, vengeful ghost.

The goddess was worshiped in many ways. There was the porca praecidanea, which involved sacrificing a fertile female pig and was necessary before a harvest. Cato indicates that sacrifices of any large food item will do, however, and suggests a pumpkin as an acceptable substitute for a pig, since it can be cut open and the seeds offered to Ceres in much the same way the entrails of the pig would be. After the offering of the "porca praecidanea", it was customary to also give the goddess a libation of wine.

The poor could offer wheat, flowers, and a libation. The expectations of afterlife for initiates in the "sacra Cereris" may have been somewhat different, as they were offered "a method of living" and of "dying with better hope".

Ceres' major festival was the Cerealia - the ludi cereales, culminating on April 19 to celebrate the growth of grain and other agricultural products. Its original form is unknown; it may have been founded during the regal era. During the Republican era, it was organised by the "plebeian aediles", and included "ludi circenses" (circus games). These opened with a horse race in the Circus Maximus, whose starting point lay just below the Aventine Temple of Ceres, Liber and Libera. In a nighttime ritual after the race, blazing torches were tied to the tails of live foxes, who were released into the Circus. The origin and purpose of this ritual are unknown; it may have been intended to cleanse the growing crops and protect them from disease and vermin, or to add warmth and vitality to their growth

Religiously, the purpose of the races and the games were to make the goddess favorably disposed toward the Roman people, so that she would give them a good harvest.

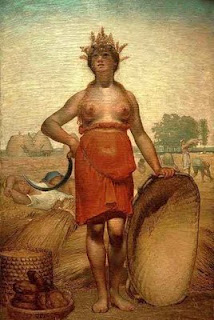

Visual depictions of Ceres were largely derived from Greek portrayals of Demeter. On two coin types, a bust of Ceres was pictured on one side, while a yoke of oxen was on the other. On other coins, she wears a crown of grain stalks called a "corona spicea", holds stalks of wheat, and is occasionally pictured with wheat and barley grains. One coin actually portrayed her wearing a modius, an instrument used to measure grain, on her head. Another pictures a bust of series on one side, and a pair of seated male figures with a wheat stalk to their side on the other. The seated men represent the official distribution of grain to the people. Annona, the goddess who personified the wheat supply, appears alongside Ceres on several coins from the imperial period. Reliefs from the Augustan period have even gone so far as to depict her as a plant growing out of the ground. In one her bust emerges from the earth, holding bunches of poppies and grain in her upraised hands while two snakes twine about her arms.

Ceres also assimilated the visual symbols of the Eleusinian Mysteries, which most Romans observed in her name. Ceres is depicted with symbols of the Mysteries, such as riding in a chariot drawn by snakes while holding a torch in her right hand.